Kienget taught me his culture’s origin story for fish, how all the fish in the sea were kept as pets by an enchanted woman, a demigod called Nendikalom. She would keep her fish children hidden away in an underwater cave that had an opening to a river in the above ground world that led to the sea. Each day before going to her garden work she would pronounce a magic spell (Auna kip – roughly translated as “mouth closes”) and all her fish children would rush in from the mouth of the cave and be enclosed within in. In the myth, two industrious culture heroes used trickery to steal Nendikalom’s fish children. They spied on her to learn the magic password and used it to open the door to the cave. They waited by the mouth of the cave and speared the fish and took them back to their village. Nendikalom saw her children escaping toward the sea and ran back and stood on either side of the bank trying to chase her fish children back into the cave, but they all escaped and now live in the sea.

I now find the fisherman’s locked door, and Nendikalom’s lost children, an apt metaphor—longing for what you have not yet had, longing for what you’ve lost. I started to understand this after I began to feel that this place in New Guinea, and the person and people I loved most while I lived there, were locked away from me. When I lost Coralie, and Kienget, I started to long in a way I had not before. Maybe not so surprisingly, when I lost these things I started to become a serious fisherman myself, someone who fished with focus and involvement. But whatever skill or concentration one brings to fishing, sometimes it seems that you need some magic to catch a fish. It seems as if you need a magic password, and those can be hard to come by. It’s the same sometimes with trying to get something back that you’ve lost.

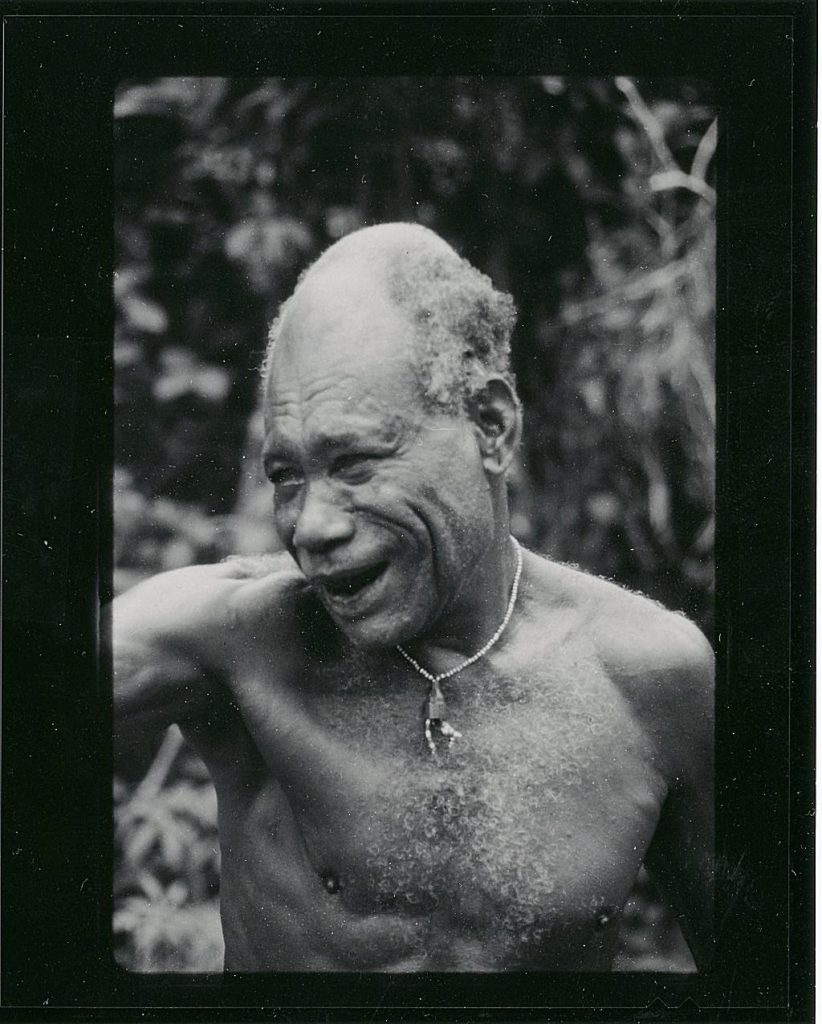

Song poet and ceremonial leader Kienget

The songs were making us softer toward one another.

The ceremonial leader and song poet Kienget taught me and my wife the fishing song during the time we lived with him in the village of Wasum in West New Britain, Papua New Guinea, while I was working as an anthropologist. For two years, my wife Coralie and I settled in a village in Southwestern New Britain to study the ritual life and culture of a people who called themselves the Rauto. For those years we lived in a thatch roof hut on a section of beach on a curving bay. Other small huts were nestled there, and the larger ceremonial houses that held the great fishing and hunting nets of the different clans. Each family’s fishing canoe lies next to the family house, always ready for a day of fishing or visiting. The edge of the rainforest of New Britain, or as Kienget would call it, Urup alang (“big dirt” – mother ground, the main or big place), lay just a few yards from the shore, leading all the way from my hut on the south coast to the north coast of the island, almost forty-five miles away. From the small veranda of my house I would look from the rainforest to the sea each morning. And each morning I would either head up through the forest to the village gardens to tend my own patch of yams and taro and banana, or I would join someone who had decided to take a break from garden work and go in his canoe to the reef, or past the reef, for a morning of fishing.

Whatever skill or concentration one brings to fishing, sometimes it seems that you need some magic to catch a fish.

The curving bay of Wasum at dusk

From my hut on the beach at dusk I would listen to the fishermen sing as they paddled back to their villages with their catch. They would sing the fishing songs, or songs called agreske that named all the fish in the sea and the birds and plants of the forest, or all of the places on the land. After the canoes came in, each string of fish would be shown and distributed to each fisherman’s extended family. The ceremony of the distribution is one manifestation of the generous spirit of much of New Guinean life, with its rhythms of gift and counter gift, fish and taro given by one clan sparking a reciprocal gift in the future1. Song ceremonies, too, were reciprocal, with one clan celebrating a child of another clan, singing to spur the child’s growth or to honor an accomplishment such as a first successful hunt. This performance would be reciprocated by the receiving clan, and so forth, so that at any given time there always seemed to be, as Kienget’s son Vatetio would say, a personal or social debt that had to be repaid or an act of exchange that had to be initiated. Like the rituals and songs of fishing, which was as sacred in the life of the Rauto as the growing of their main food, the taro, these daily ceremonies were part of a series of activities that shaped and celebrated Melanesian social time, distinguished by the reciprocal exchange of objects, emotions, labor, ceremony, and song2.

Boy marked with red ochre during taro ritual

I hadn’t set out to understand the songs. My research was to focus on gift giving, material culture and social change. As the months passed I began to pay more and more attention to the songs because, I think, their beauty and lyricism were drawing my wife and me closer together. The songs were making us softer toward one another.

The village of Wasum

The song poetry was terse, in the way of haiku. The poetry expressed feeling in ways that amplified it, the understated form itself giving you the sense that the songs contained an expanse of meaning. And the songs were full of allusions, but allusions that were barely nods to a place, an event, an object, a person, a feeling. They made you feel the evanescence of things, wherever you would encounter people singing – on a path walking up to your garden patch, out on the water fishing, when you were in the forest getting water by a stream, when you were at a night time song festival. What does that make me feel, what does that feeling mean? we would always be asking ourselves. You would almost have it… then you would lose it. It was like being a fisherman who can see the color of a fish when he gets it close to the beach or canoe but then he loses it – what was it he asks?

“It’s always about you, your adventures and your career. You don’t care what you put me through, what a place this is, what a man’s place.”

“I have to do this,” I would say over and over again, “This is the big test of my life. If I don’t do it, I’m nothing.”

I guess I could also have said, “Too bad if you don’t like it, you can go if you want, thanks for helping out so far,” and that would have been, rightfully, the end of us. But I didn’t say that. And so we turned away from each other that night and the rats played and fought and knocked over some of our food cans off the shelves we had roughly nailed up in our hut. We settled back down on our wooden slat bed and re-arranged the mosquito nets. She turned back toward me and held onto me as tightly as she could. And I didn’t know what to do. As stiflingly close as we were, we were driven apart.

It was during one of the many nights like this that Kienget showed up at the door of our hut. He wore a soft smile that night. He said he had come to teach us songs and stories.

First, he played the panpipes for us. He played a beautiful song that he said was a bit of love-magic, meant to soften a woman’s heart. I wondered if, like me, Kienget thought Coralie must hate me at that point. Then he taught us the fishing song and said we should sing it to ourselves when were having trouble sleeping. He was perhaps too tactful to say that the song would soften our hearts toward each other.

I remember his words that night, his gesture of good will. I remember these things because they were an acknowledgement of our humanity. Kienget was the first to see that we were hurting inside, and that we had not yet found our footing in this new place, either with the people or with each other.

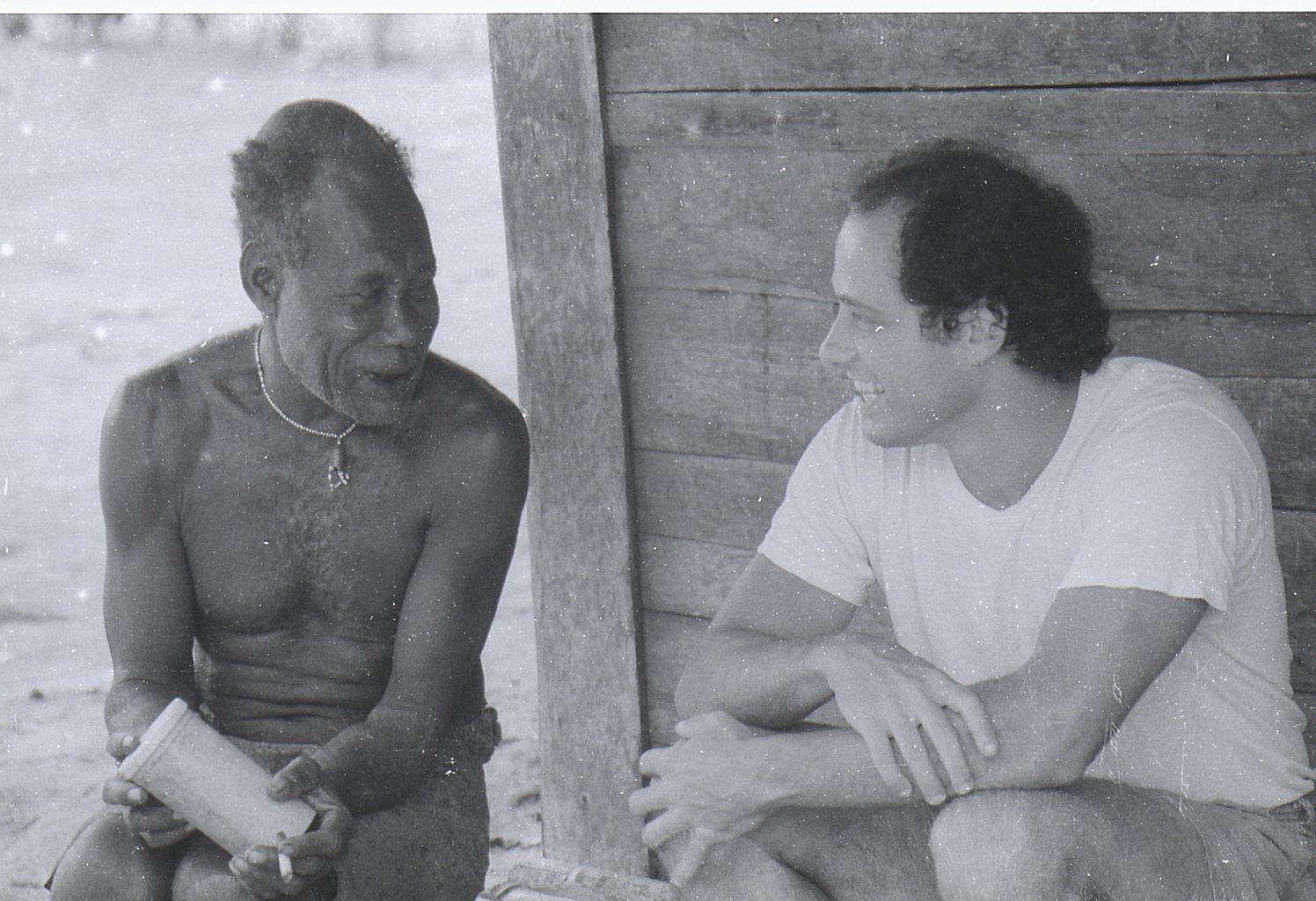

Kienget and I share a joke how to appear in a photo (pretending to chat)

These could have been the words of a caring father. They made me think of my own father and of his worry for Coralie and me. And Kienget did become a sort of father to us, very protective, though sometimes gruff and impatient with our questions and our calls for his songs and his stories. He was an old warrior who had known battle with spear and shield as a young man in the days before the missions and pacification had come to the tribes. But most of all he was a song poet and a magician. The people would say that he held all the songs, by which they meant not only that he knew them all but that only he was entitled to lead others in their performance during the many song and ritual ceremonies that made up the religion of this people. During my time in New Guinea he would instruct me in the fact that the traditional religion of his people was a religion of song – sung in order to allow children to grow and flourish, to nurture the crops and encourage the growth of animals, to send the dead on their way, to remember and to memorialize the dead, and to bring fish and game to the nets. Of all the songs he taught me, I came to like the fishing song best, and of all the stories the story of Nendikalom means the most to me. Once, I remember, when Kienget was teaching us his people’s songs he asked Coralie for a lock of her blond hair to decorate one of his prize pearl shells (a Rauto form of money). He placed the lock of her hair along the side of a beautifully polished shell, fastening it to what the Rauto call the shell’s “ear” with a closely woven small hood-like covering. I thought it a great honor for us that he asked for the lock of Coralie’s hair, as though he might be trying to weave something of our persons into the essential material and spiritual fabric of his culture.

“You will see that things will be better, and you will learn many things from us.”

So, we were becoming a part of the scene, being made part of the culture even for that moment, and connecting to the fishing and the singing, and even the tramping through the rainforest, the very roughness and difficulty of a place. Coralie said that New Guinea was a “man’s place”. She saw something that was immature about its rough, boy’s own adventure quality, but really it was the contrast between all this and the delicacy of sentiment expressed through the songs and ceremonies that threw me off balance and that captured me. The feeling of being captured by something or someone had always been rare for me.

Female puberty/initiation ritual.

I tend to draw back from people, to be reticent. I don’t usually throw myself into things, causes, people, places. I don’t join. Even my choice of profession had offered some promise of psychological and emotional distance, an escape hatch from my family, from the commitment of an early marriage, from my own culture. Here I was, escaping, yet at the same time I was being drawn into another world and place, and drawn into greater intimacy with Coralie and with Kienget, our guide, teacher and protector. He and Coralie and I were becoming part of a team. The first step was his gift of the fishing song.

***

In Southwestern New Britain the rules of fishing magic stipulate that the head clan magician come to renew the magic of the nets a few days before a fishing trip. He does this by means of the fishing song, which is really a spell. A number of other song spells are also recited as protective magic during the ritual renewal of the nets, to protect against the ill will and evil potential actions of rival fishermen, who are interested in making the nets of their competitors repellant to fish rather than attractive and ensnaring.

The fishing song, Kienget informed us, tells of how certain beautiful reef fish become drunk with enthusiasm when they begin to feed, how their back fins break the surface water, and how their tails slap the surface, as if the fish are performing a dance to express their happiness at hunting down the bait fish. The song encourages the fish to be energetic and enthusiastic in these ways, and so, easier to see and capture. In the song and the fishing spells, the net is compared to the mouth of a giant grouper, the highest-ranking fish of the reef, whose orders are to be obeyed. The reef fish are drawn toward the net by the grouper and enter the net as these fish enter the mouth of the grouper when they become his prey.

The rhythm and tone of the song are soft and slightly melancholy. These reminded me of many of the love songs I heard and recorded in New Guinea. I came to think of the fishing song as a love song, sung to charm and to seduce the fish into the net just as in love songs the singer does his best to charm a woman’s heart, doing his best to draw her to him. A free translation of the fishing song is as follows:

|

Oh reef fish, (species names) your fins break the water’s surface as you feed and rejoice. The grouper orders you forth. You enter my net as

The fish Palo (species) enters the Grouper’s mouth.

The fish Karkar (species) enters my net;

The net’s power draws you to it. The nets are heavy with fish (They weigh the canoe down as we make our way back)

|

Ieueruer, ongua Uaiio lom nara ei, ei

Uai oh lom Uai oh lom Ieueruer,

|

A clan’s fishing net

The fishing song wasn’t just a kind of love song. It was a memorial to lost people, to trying, failing, losing and succeeding. It memorialized effort, the throwing of oneself into a task. It memorialized the fisherman’s hopes and his dashed hopes, and also letting go, which is something all fishermen have to learn to do. Its lessons are like those of the mourning song that Kienget taught us:

I leave you now,

Smoke rising: these things are yours:

(no, they go with you)

Spirit masks (kamotmot) mourning the death of the man Pokol

Some of the fish were as beautiful as the poetry sung to entice them. There were queen fish, silvery green with yellow reflections, and bream, neat and powerful. Once in a great while there were yellow and white jackfish. Sometimes we would take parrotfish, who used their beak-like mouths to break off and eat coral. There were groupers and grunts and needlefish as well. The fish were all light and color and flash as they came into the net. The vibrancy of their colors and the strong current of energy that animated them added drama and excitement to the fishing.

What does that make me feel, what does that feeling mean? we would always be asking ourselves. You would almost have it… then you would lose it. It was like being a fisherman who can see the color of a fish when he gets it close to the beach or canoe but then he loses it – what was it he asks?

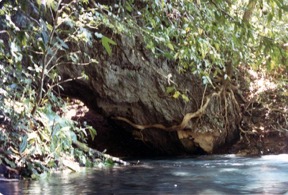

We took a canoe by sea to the opening of an inlet that led to a curving bay at the back of which was Nendikalon’s salt stream. After beaching the canoe we followed the stream to its source, about a half mile inland. The cave emerged from the side of a cliff, and there was a great rushing sound from its mouth as the underground river forced its way up and out into daylight. You could hear the sound of the rushing water from a long way off, and you knew you were getting close to a special place.

We stood watching to see if any fish might swim past. Kienget said we would be able to see salt-water fish as well as fresh water ones swim through the cave’s mouth, though we were over a half-mile from the beach. But we didn’t see these fish. Apparently Nendikalom had released them before we arrived. Or perhaps the two tricksters who learned Nendikalom’s spell for opening and closing the door had taken them.

The opening to Nendikalom’s cave

Kienget spear fishing in Nedikalom’s river

During a return visit we found that a timber-cutting outfit had established itself near the village. The loggers had made pens for keeping the cassowary that had been frightened out of the forest, and they had brought in many birdcages to hold the various species of parrot and other birds that had lost their forest home. The loggers were going to sell the birds, I was told.

It was a shock one day to see a huge old repurposed oil tanker pull offshore from the little curving bay; old growth rainforest timber was towed out to the ship for export. It was more of a shock to learn that a New Guinea friend, the gentle Plasio, who cried quietly as he said goodbye to Coralie and me at the end of our first field trip, had been killed in a senseless timber-cutting accident. It seemed to me that I was losing this place as I had originally experienced it. I was losing the space it had claimed in my imagination. I’m not sure my Rauto friends experienced this same sense of loss. They wanted a different sort of life than the one they had been living. And, though ecological and other sorts of ruin were coming into play, this was basically their choice – however much I worried they were being taken advantage of. At the time of my second field trip I began to be gripped by a nostalgia for the way things had been when I first came to live in the village. I realized then that these feelings were selfish, if not patronizing on some levels, but there you have it. I was very concerned that there were no fishing trips with Kienget that second time, as a section of reef had been killed off by mud and runoff from the logged over forest. I suppose that fact stood in for my grief over what was happening, making visible to me what I was feeling inside. Again and always, fishing is a symbol for other things for me.

The fishing song wasn’t just a kind of love song. It was a memorial…

What hurts most is this thought I keep having that the other person whom I cared most about during this time, the song man Kienget, has died by now. There are many losses to bear in this life but these cut me particularly deeply.

Kienget’s song poetry is still with me. I have his songs in my head when I go fishing, though perhaps they should only work for someone fishing with a net rather than a rod, reel and lure. I sing to the fish anyway and I picture Kienget fishing alone in his canoe, longing to open the sea’s door and, perhaps through some magical trickery, to open Nendikalom’s cave and gam gam, or steal, her treasures. At these times I think I’m trying to get something back that I’ve lost, and that I’m not going to be able to see through to the other side, peer through the mirror and take what I need. I feel a real longing for Kienget, and for many other things. These things elude my grasp as I reach for them.

***

- ngot nondro – lit. “nose comes back” – a gift exchange – but each different type of compensation or exchange has a different linguistic term, marking the importance of the gift to Rauto culture

- For more on Melanesian social time, see To Remember the Faces of the Dead: The Plenitude of Memory in Southwestern New Britain (T. Maschio).

- They said we looked like spirits, or ghosts, freakish to many (Igle – tambaran in Tok Pisan – meaning spirit, uncanny, monster).

- Conical masks made of coconut tree fiber, each with its own characteristic face design, kamotmot are used in dancing and in the men’s secret society.