The frame is not big enough. The camera cannot capture desire. The light is not enough to slow Sabrina’s hands as she fingers the beads on her dress. The aperture is not wide enough to speed up the shutter or narrow the depth of field. Still, this is but a fraction of a second in her six-year-old life.

We are taught art by its imperfections. We move around the photo mounted on the black cardboard and point out its flaws. We make a list of mistakes. We cannot edit this photo enough to fix it. Garbage in is garbage out, we say of Photoshop’s magic. We cannot recapture this moment again. But next time we will be better.

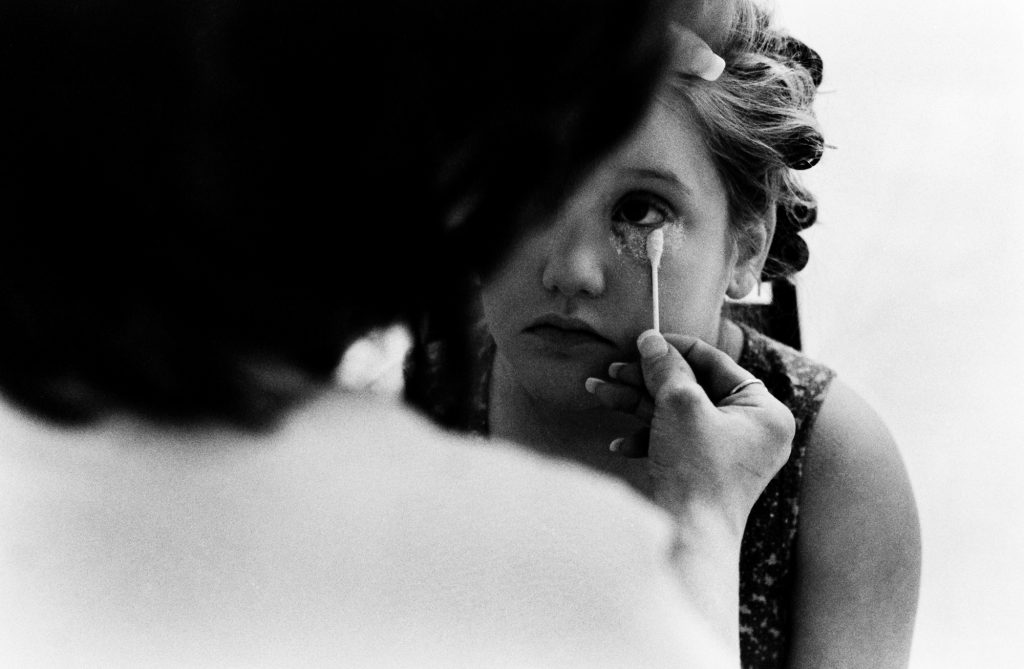

It has been nearly twelve years since I met Sabrina and her mother Michelle. Every time I see this photo, I see the blur first before the light. Then, the direction of the light, the way it pours down Sabrina like water over a cliff. Her shiny lips, false eyelashes, fake hair. Her mother once told me the men she worked with thought Sabrina was 17 when they saw her headshots.

I want to linger on the wiglet on top of her head, the highlights laced through the curls. She is young for fake hair, augmented beauty. Wiglets belong to women who start losing hair in their forties, strand by strand abandoning their heads till they are not just thin but bald. Not to six-year-old girls with thick virgin hair.

2.

I mean to write about beauty, but it is inseparable from mothers. Inherited from our mothers. Taught by our mothers. We learn to wear the pretty lace socks because our mother puts them on our feet while we watch cartoons. We learn to look in the mirror. We learn to frown. We are insecure about what our mothers are insecure about.

Maybe it is terrible to say I picked this duo in the America’s Cover Miss pageant in Owensboro, Kentucky because of their imperfect bodies. Don’t mistake me. This is not a criticism. Sabrina is still one of the most beautiful children I’ve ever met. She was also a bit bigger than the other girls. I think I remember that Michelle had gastric bypass surgery, but after twelve years, I cannot be sure of anything I did not write down. All I have is my memory and these photos.

I’ve always been afraid of women who are too thin, convinced they’re judging me for taking up too much room in the world. This fear is based in reason, in experience, in the fit woman on the plane next to me recently, texting a photo of my lap because I was using a seat belt extender. I’ve never been thin, not even when I was a girl. Baby fat led to adult fat. My fat has been less and more and less again, but never nonexistent. Fat is a word I want to reclaim, a truth based in the cellulite on my thighs and the half-tire around my waist, but the word still smarts when hurled at me.

I do not want to base my self-worth in the numbers on my scale, like my mother. Unlike my mother, the numbers are not small. I do not exercise when my husband cheats on me, taking classes every evening at the YMCA. I do not exercise at all right now. I do not have a husband or a boyfriend and I never have. I look down at the soft belly fat and thighs that rub together and can’t imagine anyone wanting me for longer than a night.

3.

Photojournalists learn equivalent exposure first, how aperture and shutter speed and film speed expose the light-sensitive film plates in our cameras. A good photo depends upon light and composition and moment. We will see the light, our professor says. After we see the light, we won’t see anything else. Where the light comes from, where it falls in the frame. We learn to frame the photo with the foreground or to put the subject in the distant third of the photo or to crop close, go wide. We look for the singular moment in time. We hope for perfection.

I see the many ways this photo falls shy of perfection, how large the head in the foreground is, how dull the light is. Still, some singular moment amongst the hundreds of pages of negatives now resting in my mother’s garage must’ve caused me to pick this one photo.

My notes say Diana charges $50 every time she touches Sabrina, usually three times a weekend: the initial makeup, the touch-up, the crowning ceremony. Diana is the only one Michelle trusts. Now add up the other costs: the fake hair, fake eyelashes, fake nails. Photogenic pictures cost $800; dresses, $1,000–2,000; hotel stay, $80 a night; on-stage professional pictures and age-group video, $80. It seems too much to spend on a child, but my working-class mother spent $16,000 on my professional photography equipment while I was an undergraduate. Perfection is costly.

4.

Zoom out, we’re told. Long shot, medium shot, close shot. A good story uses all three.

I remember this day, this moment. Sabrina couldn’t play with her doll until she practiced her stage walk. Some kids are promised trips to the hotel swimming pool after the pageant. Everything is a series of trade-offs. We lose obscurity but we gain poise, we hope. We become aware of the way eyes follow us on stage.

I abandoned photojournalism a year after I shot this photo story. I started writing, first because it was fun and later because I had to. I was restless without it. The first time I was asked to read my writing on stage, I gripped a podium, terrified of the eyes on me. The second time, I knew there was no podium. I told my therapist I wasn’t ready to read my writing on stage again, by which I meant not now and not yet. I wasn’t thin. I didn’t want anyone to look at me. She asked me if there was anything I could change in a week. I could lose a few pounds. I paused, unable to think of anything else. She said, “You must accept the way you look.”

5.

It would be easy to tell a different story. Up until this point, I could’ve said this is coercion, this is JonBenét Ramsey on a smaller scale, this is a mother projecting her desperate desire to be beautiful on her six-year-old daughter.

Would that be wrong? Don’t all parents project their desires on their children?

My father wanted me to be a doctor or a lawyer, but mostly a lawyer because he was a cop. He got a daughter who was a photojournalism major, a French major, an English minor. Later, a religious studies major, an English major. A creative writing graduate student. He would’ve preferred anything but a writer, because I write nonfiction.

It has been eleven years since I left photojournalism behind, and I still don’t know why. I think I was afraid I’d spend my entire life behind the camera instead of in front of it. I didn’t want attention, but I wanted to stop hiding. I wanted a voice. I wanted to tell my own story, the one hidden in my coat like a pocket full of rocks in a cold, cold sea.

I’ve always told the truth, but now I use words instead of photos.

The truth is that sometimes Sabrina liked the pageant. The truth is sometimes I judged her mother and sometimes I thought there wasn’t any harm in six-year-old girls playing dress-up. Sabrina would learn to perform her gender eventually anyway. The truth is complicated.

6.

We learn to live with our cameras. If we don’t sleep with our cameras, we sleep with police scanners if we’re truly dedicated. We bring our cameras to breakfast, to campus, to parties. We are the college kids with boxy cameras shooting the couple in the corner making out. We are told to study photo books. We spend our days in the photo lab, looking at our classmates’ photos. We buy our film in bulk and roll it in plastic canisters ourselves. We hand-process film in steel tanks, agitating, rolling, shaking. We stand in the half-dark, the chiaroscuro of our lives. Our clothes become stained brown with fixer, rotten like eggs. Our classmates become lovers, shooting photos together, and photography skill becomes almost sexually transmitted.

The conscious becomes the subconscious. “Then comes the supreme and ultimate miracle: art becomes ‘artless,’ shooting becomes not-shooting, a shooting without bow and arrow; the teacher becomes a pupil again, the Master a beginner, the end a beginning, and the beginning perfection,” Zen in the Art of Archery promises.

Photography has always been described with hunting words: shooters, shooting, feature hunting, even snapshot—a gunshot fired quickly and haphazardly, according to Stephen Bull’s Photography. Polysemous words cause us to consider all meanings, to pause at context.

Ultimately, we live by instinct as photographers. Whether by subconscious or accident, we produce subtext. Look at Sabrina’s crowning moment for her age group and the “Judges’ Choice” instead of Ultimate Grand Supreme, the award of stacked superfluous superlatives. Her face in shadow. The beginning of the end, Michelle says, because she is becoming aware of her appearance.

7.

“I wasn’t sure you were a photographer till you showed me this photo,” my friend Dave said. He was chief photographer of one of the best small newspapers in the country. Now, I always gravitate towards this photo.

We think we have an eye, but we don’t know for sure till someone confirms it. We don’t trust ourselves to know what’s good. We need constant affirmation after being torn down so often.

I can’t stop looking at Sabrina’s face in the mirror. I can’t stop thinking about how I look in the mirror: zits first, red ones and healing ones and discolorations where zits were. I’ve never been like the women in those acne commercials but I’ve always broken out constantly. Like my father. He has scar tissue on his jawline, deep cysts that formed land and then died, like extinct volcanoes. A dermatologist once cut open his face and found a tight ball of hair underneath the skin. I am terrified that will happen to me one day.

I see the beginnings of wrinkles around my eyes when I smile. I’ve always looked six or seven years younger, but lately I look closer to my age than ever before. I am 33. My chin doubles when I gain weight—though I have never lost my neck. There’s a small mole—birthmark—next to my nose. My face will never have symmetry. I see hair of my chin and upper lip I am always plucking. Eyebrows I never pluck. Not-white teeth.

Last year, my dentist drilled so deep in one of my cavities that he irritated the nerve. When the local anesthesia wore off, I was in so much pain I almost begged for an immediate root canal. Instead, my dentist gave me Tylenol 3, the first prescription pain medicine I’d had in years. On Tylenol 3, I was happier than I’ve ever been, a singular moment in my life. I looked in the mirror and saw the soft glow of sunlight reflected on me, like someone was following me around with a soft box, the gold ring around my dark blue eyes, my high cheekbones. I knew I had flaws, zits and wrinkles—but they weren’t important. I was no longer a collection of flaws but a beautiful person. It was terrifying.

8.

We are told the act of being in a room with humans changes the room. We strive to be the clichéd fly on the wall, the quiet observer, the visible invisible. But we are told that if we are too quiet, our subjects will be wooden. So we talk when we’re not shooting photos. They see us, adopt us, offer us Iranian food at a Persian New Year party or fresh milk from their cows or a chair to sit on at the pageant. We accept that we have changed the situation by being there, though we have a code of ethics. We never tell someone to move. We don’t ask anyone to hold hands or kiss. We don’t use Photoshop to combine our two best photos. Whether or not we open the curtains for daylight, even, depends upon our own code of ethics. We must all have our own code of ethics.

This is not much different from creative nonfiction, where we tell a story based on memories, which change with time. If we quote, we are quoting journals or we are quoting from memory. We use the lower-case “t” for “truth.” We call this emotional truth. We believe in intentions.

My memory says these kids were bored, in between pageant events, good friends. My notes from twelve years ago say Sabrina’s friends are named Elegance and Diamond, sisters in the pageant circuit. Elegance, the one on the left, won Supreme Overall winner. My photo shows that Diamond knows I’m there, not as invisible as I’d hoped to be.

9.

At some point, we are alone. Our photography professors and writing professors have no more left to give us. No one has the care and time we have for our own art. If we don’t make it, no one will. We edit the photo story on the floor, rough LaserJet print-outs in place of darkroom or photo printer prints. We edit our writing on the floor, the wall, the desk. We are terrified alone, but we apply what we’ve been taught.

I know Sabrina is alone on a stage, and I don’t mean to read too much into her playtime or her pretty doll. She has downtime in between Diana’s makeup sessions. There are at least four others Diana works on. And yet I can’t stop thinking that when she is on stage, she is alone again. She must do as she has been taught, and only she can do it. She must mimic the pretty doll.

10.

I do not think Sabrina was talking on the phone to a real person. I think, perhaps, she was playing, whether for my benefit or for her own. I know she lived in a trailer in Kentucky. I know she was still, at heart, a six-year-old girl in a messy room.

We are taught many things as photojournalists: to try every angle, to double-check names and spellings, to be prepared with extra cameras, extra batteries, extra film, extra pens and sharpies and notepads and even gaffer’s tape. We are taught to be perfect photojournalists who document imperfect lives. I could never be perfect enough.

This is scarily self-revelatory. I don’t think I could be so brave. Brava.