Before his name became associated with his murders, I met Al Castaneda. I helped him get stronger, I’m sad to say now. He came into Iron Lifts one June morning wearing baggy blue sweats, which, okay, it’s not unheard of, guys in full sleeves like that, even in the summer. Still, we didn’t even have AC. Just a couple of drum fans and a gate that opened to a loading dock.

Ten bucks for a workout, fifty-five for a month. Sign a waiver, you were a member. Not bad for New York. No initiation fee, either. Also, zero sales pitch for a BMI calculation, a trainer, a lesson, whatever. We offered that stuff on our signage, though. Al took the lesson.

You’ve seen the pictures of him, or you can. Dark brown eyes so deep-set they look driven into his skull. Scraggly dark hair stuck to his forehead, bony face perpetually two or three days overdue on a shave. Kinda yolked for his frame. He weighed maybe 150 when I met him, though. 5’10”, thin wrists. At first I took him for one of those scrappy, unkempt-out-of-spite, “Yeah, so? Wanna fight about it?” types of guys. Maybe a local busybody coming in just to satisfy his completist domain of the neighborhood. Whatever. No frills, no judgement. That’s our thing. I welcome all newcomers to Iron Lifts.

Though had I known Al Castaneda was a goddamn serial killer, I would’ve put him in a choke hold. Then maybe a pile-driver. Or the Boston Crab.

The headline above Al’s photo read: Presento Asesino Detenido en Nueva York. I’m terrible with faces and Spanish, so I had the confused idea that this Albert Amos Castaneda was some cartel hitman who’d been on the lam in New York. But he looked familiar. I finished up and brought the iPad outside to show Lizzie and Cassandra. Lizzie set the tablet on a towel on the ledge of the pool and we gathered around the screen to read. Castaneda had been found on a wooded hillside in upstate New York, laying near the deceased victim, a twenty-six year-old female jogger who’d been missing for a day and a half. Apparently, Castaneda had killed her on a trail and then injured his back trying to drag her body up the hill. Authorities reported that Castaneda had used the jogger’s cell-phone to call for help.

“I can’t wait to hear his explanation,” Lizzie said.

So far, there wasn’t one. What there was (though these details had yet to reach the public) was a shallow pit and a shovel at the top of the hill. Also, a telling arm’s length from where Castaneda was discovered, poorly buried beneath some leaves and twigs and whatever else he could manage to get ahold of in his supine state: A bloody hammer, a bloody switchblade, and a bottle of KY. So.

Ross came back and I filled him in while the girls got dressed for the trip. “Doesn’t look familiar to me,” he said. “He come into the gym maybe?”

Felicia came back on the line. “Al Castaneda,” she said. “Address on St. John’s Place. Date of Birth, 4/22/77.”

I looked at Ross. “He used his real name.”

“No law against getting strong,” Ross said.

“Alright, well, Felicia,” I said. “Can you let the police know he worked out at Iron Lifts and that I gave him a couple of lessons? That was the extent of our relationship. I fly back into Newark tomorrow evening. Give them my cell but I don’t want to incur roaming charges for something that can wait. He’s already caught, right? So.”

“That’ll get us crashed, Mexican Siri,” he said, and turned the device off.

We passed our second checkpoint of the drive and were for the second time ignored by police armed with machine guns. Every few kilometers we passed another gargantuan entrance to a resort, gates to competing paradises plunked down along the jungle shoreside by corporate providence.

“It seems like we can’t really see what’s available until a month out,” Lizzie said. “All the postings are for places that want tenants in July.”

“Yeah, or now. Like this second,” I said.

Mark’s place had some of the first fairies that began appearing in homes along the eastern seaboard in January.

Their chemistry with Lizzie was so favorable that, in May, when I asked Mark if Lizzie could stay with us from July through October, he told me she could move in as soon as she wanted.

“The fairies will be happy,” Cassandra teased. They loved Lizzie, the fairies. They answered only to the names that she gave them. You’d think that there’d be some reciprocation there, what with the ethereal positivity, but no. Lizzie didn’t give them kind names, and it was too late to change that.

“Oh, they’re fine,” Lizzie said, with newfound diplomacy. “Mark is doing us a huge solid. We’ll be able to save a ton on rent.”

Dwelling within the sanctuary were not only a dozen or so spider monkeys but a couple of dogs, a horse, a donkey who didn’t like the horse, ducks, a crocodile, and, with the most generously apportioned acreage, (and) a testament to the founder’s integrity, some white-tailed deer. Some of the monkeys engaged us, but only provisionally, as if they were merely ascertaining that this new group was the same old news. A female, whose terms of rehabilitation permitted us to interact with her through the fencing of her enclosure, gave me a moment with her prehensile tail while Ross rubbed her back. Her tail was strong as a tongue, and more elegant, wondrous as pure invention, realer than me. Her abusive past gave her little savvy in the ways of true monkey business. Her reintegration was to be measured and supervised. She would be weaned off of us.

Other monkeys were free to roam the sanctuary. We were to leave them alone. I’d heard that the average chimpanzee could pluck the limbs from the world’s strongest man, but our guide claimed that even a spider monkey would make short work of a human in a fight. Ross and I disputed this in private, but damn could they swing and climb. Even the fat one, whose previous owners gave him nothing but Snickers and Dr. Pepper, moved gracefully to his fruits and vegetables, which were strung up in a bucket from his enclosure’s ceiling to encourage exercise.

Every morning but that one, we walked to the same beach club and rented chairs. We lay for hours in luxurious boredom. We drank Mexican beer and margaritas. We returned to the water again and again. I’ve never wanted to be in a place’s sea so much, so often. Every night we strolled a dense thoroughfare, dumb as bees glutted on nectar, beckoned every block for souvenirs and drugs. Builders built around the clock. Dogs ran along without leashes. We ate Mayan and Mexican and I thought I might end up poisoning myself on camarones, but the pizza held its own too and the Thai tasted like Thai. When we were only drinking, the bars would still feed us for free. It all lasted one minute, but what a minute.

Our last night there, we drank mescal and black tequila at a sidewalk bar, talking of nothing but Al Castaneda. I’d decided that he wore full sweats because he made a practice of not appearing to be as strong as he was. Lizzie mentioned that Ted Bundy was similarly cagey, even wearing leg casts to throw his victims off. I alternated between blaming myself for helping Castaneda and blaming myself for not seeing the signs. Everyone absolved me again and again, but already it was as if my memories of him took on the pall of complicity. “Don’t let your knees cross in front of your feet,” I had told him.” “Don’t bow your back. Tomorrow you’re either going to wish you were dead, or wish I was dead.” He’d found that pretty funny.

The TVs in Newark International showed coverage of developments in the Al Castaneda case. I only caught the gist because we were hustling from customs to the shuttle to try to make an eight o’clock train to Penn Station. The following train would leave in an hour. Authorities had found another body, this one buried in a cave in the Catskills, which they attributed to Al. They cut between a reporter standing on a dark road that could’ve been anywhere, and a map of New York State. We missed the train. The station bathroom was out of order and I was beginning to feel then what I’ll describe as moderate discomfort.

“The Mountain Lion,” Lizzie said, looking at the news on her phone. “Why would they give him a name that sounds cool?”

New Jersey Transit was so crowded that we had to stand in the vestibule. At Penn Station I began missing my brother and Cassandra the second they left us to take a cab to Gramercy. Lizzie wanted to drop her bags off and shower before coming over so I took the 2 into Brooklyn alone, hardly able in my increasingly alarmed state to feel much more than a kind of promissory guilt for not insisting on accompanying her. Still, she had two female roommates with one bathroom between them and no lock on the door, so.

It didn’t get urgent until the train finally ground to a stop at Franklin Avenue and coughed open its doors. Isn’t it funny how your body knows when you’re close to where you need to be? It starts trying to set things in motion. Like, in case you forgot? I tried lying to myself, saying it would be another hour, hoping it would put me back in a holding pattern, but no dice. Crash landing, ready or not. Adding to the torture was my inability to hurry, so tenuous did my control feel.

I got into the bathroom and immediately shut and locked the door, but not before Dermatitis and Foreleg zoomed in. Ass Ears and Package thudded softly against the outside of the door. “Dammit, guys,” I said. I turned on the faucet and sat down on the toilet. They hovered in front of me at eye level, these beings the sizes of cigarettes, faces of imploring goodwill and airy gaiety. I shooed them away. They flew up to the shower rod at sat there watching me give myself over to release. Barely distinguishable above the running water and my own noise, I heard their high-pitched babble as they discussed whatever they thought I was doing. As far as I knew, these fairies didn’t poop. Nor did they have genitalia, as was evidenced by Package, who Lizzie had named for his eschewal of a loincloth. They both started to cough, and Forelegs’s lavender wings beat reflexively, which caused him start to fall back until Dermatitis caught and steadied him. Or her. Or whatever.

I woke to soft knocking on my bedroom door. Lizzie stuck her head in. Mark’s little wards lay in a heap on the pillow reserved for her. “Mark’s guests were hoping they might be allowed in for a visit,” Lizzie said. “The fairies were part of the draw in getting the girls over here to read his drafts.” I passed them in the hallway, four women quietly waiting in a line. On each still face, beneath the restraint of politeness, beneath even the anticipation and wonder, a childhood self pressed forth, reaching, hopeful, maybe not without magic of her own. In the living room, Mark was scribbling notes to more TV coverage of the Al Castaneda case. A third body had been found in Cold Spring. A search had been initiated for a fourth in Black Rock Forest.

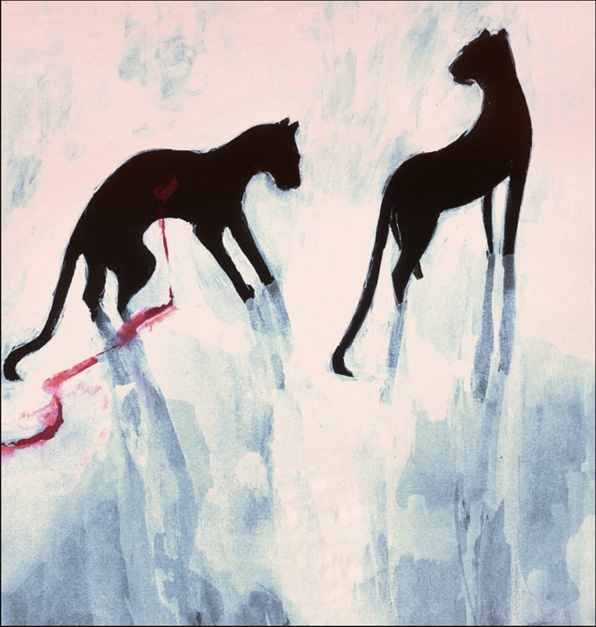

He took his baseball cap off and ran a hand over his bald head. “Ever since this came out,” he said, not bothering to finish his thought. He muted the television. On the screen a reporter interviewed a park ranger in front of a line of service vehicles. “I want it to be about the victims, the girls,” he said. “All I can think about now is how they might’ve seen him. Someone is dragging you away from your life. With what consciousness you may have left, what do you sense from him? Rage? Arousal? Or just a shadow? Impersonal and hateful at the same time, no man at all, just a nothing in the form of a man, an it, propelled by need and narcissism.”

I told Mark about my time with Al Castaneda in the gym. Mark mentioned that they’d found a power rack and plates in his apartment on St. John’s Place. The risk for injury greatly increases once you get serious about weightlifting. If you wrench up on a dead lift and the bar slips from your hands, you can really do a number on your lower back. I imagined the incapacitated monster lying on the wooded hill. Waiting out the hours to see if he would get better, or die, or use the cell phone of the woman he’d murdered to get someone to rescue him.

“Shall we go see what all the fuss is about?” Mark asked.

“Naw, man,” I said, turning the television’s sound back on. “Let’s leave ’em alone.”